INTRODUCTION

A trademark is a visual representation of a brand and acts as a source identifier for consumers, indicating the origin of the goods and services. The word ‘Trademark’ has been defined under section 2 (1) (zb) of the Trademarks Act, 1999 (hereinafter “TM Act”) as a mark which is capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others, and may include the shape of goods, their packaging, and the combination of colours.

In India, trademark registration is not a compulsory requirement in India. However, it is advisable for a brand to register its mark to avail the benefits that come with it. The Registrar may refuse registration under absolute (Section 9) or relative (Section 11) grounds. Within the absolute grounds, Sections 9(1)(a) and 9(1)(b) often confuse; however, they address distinct issues, non-distinctive and descriptive marks. This article examines their differences with supporting case law.

GROUNDS FOR REFUSAL OF TRADEMARK REGISTRATION IN INDIA

The registration of the Trademark can be refused under section 9 and/or 11 of the TM Act.These provisions are equivalent to sections 3 and 5 of the UK Trademarks Act, 1994 and Articles 4 and 5 of the European Union Trademarks Directive 2015/2436.

The Absolute Grounds for refusal (Section 9) are based on the inherent characteristics of a mark. These grounds are focused on the nature of the trademark. While these grounds are varied, the most commonly debated are Sections 9(1)(a) and 9(1)(b), which often overlap in practice but are conceptually distinct.

The Relative Grounds for Refusal (Section 11) are based on the potential confusion caused by the similarity between a new mark and an existing mark. The main difference between absolute and relative marks is that the absolute grounds are applicable where the issue is with the mark itself, and the relative grounds are applicable where the issue arises because of the conflict between two or more marks.

SECTION 9 (1) (a): NON-DISTINCTIVE MARKS

The marks that are ‘devoid of any distinctive character’ are refused registration under this sub-section. Non-distinctive marks are also known as Generic marks, which are covered by the phrase ‘devoid of any distinctive character’. The distinctiveness in the mark must be so that the goods and services of one entity are capable of being distinguished from those of another. For example, a bakery company wants to register the trademark ‘Bread’, it will be refused as Bread is a generic term which is just naming the product itself and cannot distinguish one bakery’s goods from another.

The distinctiveness is the most important character of a trademark, which sets it apart from all the other marks present in the market. There are two ways in which a mark can be of a distinctive character, i.e. Inherent distinctiveness and Acquired distinctiveness.

- Inherent Distinctiveness: Inherent Distinctiveness is the one that a mark has in itself. This means that the mark is distinct and strong in its character without needing any proof of prior use or established goodwill. For example, the term ‘Britannia’ for a bread brand does not in itself suggest that it relates to bread, yet it successfully distinguishes one bakery’s products from another. On the other hand, using the word ‘Bread’ as a brand name for a bakery business would be considered generic and, therefore, refused registration under the TM Act.

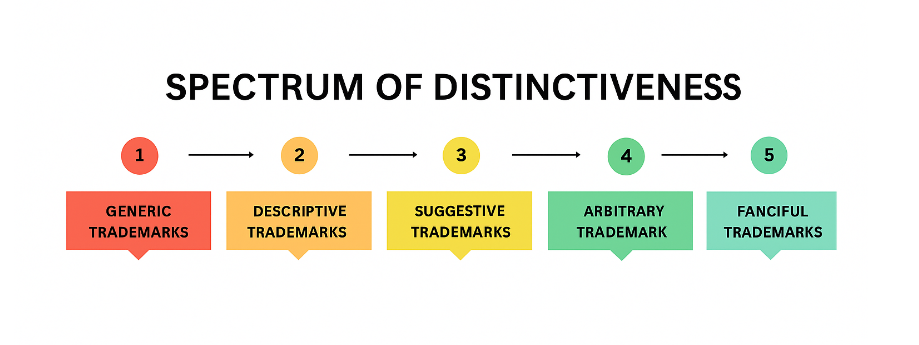

The case Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., 537 F.2d 4 (2nd Cir. 1976) established the ‘Abercrombie classification’ or ‘Spectrum of Distinctiveness’, which ranges from the weakest to the strongest marks in five categories, namely, Generic, Descriptive, Suggestive, Arbitrary and Fanciful Trademarks. This spectrum reflects the registrability of trademarks, with generic marks being the least capable of protection and Fanciful marks being the most readily registrable.

2. Acquired Distinctiveness: The trademarks falling under this category of distinctiveness are those that develop their distinctiveness through prolonged usage in the market and thus are popular among their customers. These kinds of marks are initially not registrable due to not being inherently distinct; however, they develop goodwill through long and continued usage, thereby acquiring secondary significance. These kinds of marks are often required to prove their distinctiveness through their sales figures, advertising, and consumer surveys. For example, if a company has been selling under the mark ‘Fresh Bread’ for over 20 years, invested heavily in advertising, and consumers now associate the phrase exclusively with its bakery, the mark may qualify for registration. Although ‘Fresh Bread’ is descriptive and would ordinarily be refused, long, continuous use and substantial consumer recognition can establish acquired distinctiveness.

In Imperial Tobacco Co. v. Registrar of Trade Marks (1968), the Calcutta High Court refused registration of “Simla” for cigarettes, holding that prominent geographical names cannot be monopolised unless strong evidence of acquired distinctiveness shows they have become source identifiers.

SECTION 9 (1) (b): DESCRIPTIVE MARKS

These marks are explanatory in nature. They consist only of words, symbols, phrases, or signs that explain the characteristics of their goods or services, such as their kind, quality, quantity, values, geographical origin, etc. These kinds of marks are often refused registration due to the lack of distinctiveness. However, they are registrable in case they prove their acquired distinctiveness, as discussed above. In the case of Anjay Bansal v. Assistant Registrar of Trade, 2023 SCC OnLine Mad 7463,

the above-mentioned mark was challenged under section 9 (1) (b), since the mark was used for Human resources services, and it was descriptive in nature as it is named ‘PeopleSource’. However, it was accepted by the Madras High Court for registration based on its continuous use since 2005, relying upon various invoices and an annual report. Similarly, the Supreme Court in T.V. Venugopal v. Ushodaya Enterprises Ltd. (2011) recognised that the Telugu word “Eenadu,” though descriptive of “today,” had acquired secondary meaning through long and continuous use, making it registrable.

KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN GENERIC AND DESCRIPTIVE MARKS

- Ground of Refusal: Section 9(1)(a) refuses registration to marks that are devoid of any distinctive character, meaning they cannot distinguish one trader’s goods from another. Section 9(1)(b), on the other hand, refuses marks that are descriptive in nature and merely explain the qualities, characteristics, or purpose of the goods or services.

- Nature of the Mark: Marks under Section 9(1)(a) are usually generic terms that are too common to act as identifiers. For example, ‘Bread’ for bakery products would fall into this category. Marks under Section 9(1)(b) are not generic but descriptive, such as ‘Fresh Bread’, which conveys the quality of the product rather than serving as a source identifier.

- Legal Test: The test under Section 9(1)(a) is whether the mark has the inherent ability to distinguish one trader’s goods from another. The trademark ‘Bread’ fails this test as every bakery uses the term. Under Section 9(1)(b), the test is whether the mark merely describes the product’s characteristics instead of functioning as a badge of origin. ‘Fresh Bread’ fails because it conveys a feature/quality (freshness) instead of pointing to a single source, such as a brand name like ‘Britannia’, which consumers immediately associate with one business.

- Underlying Policy: The policy behind Section 9(1)(a) is to prevent monopolisation of words that are too common or generic for all traders to use. In contrast, Section 9(1)(b) ensures that descriptive words remain free for all traders to describe their goods or services without restriction.

- Possibility of Registration: Although both provisions prohibit registration, they allow an exception where the applicant can prove that the mark has acquired distinctiveness through long, continuous use and consumer recognition. Thus, while ‘Bread’ is unlikely to ever acquire distinctiveness, a descriptive term like ‘Fresh Bread’ could potentially be registered if it has gained secondary meaning in the market.

CONCLUSION

The distinction between Section 9(1)(a) and Section 9(1)(b) is subtle but crucial. While the former targets marks that are inherently incapable of distinguishing goods or services, the latter prevents monopolisation of terms that merely describe the characteristics of products. Both provisions ensure that trademarks fulfil their essential function as source identifiers without unfairly restricting competitors from using common or descriptive language. At the same time, the law allows descriptive marks to be registered if they acquire distinctiveness through continuous and substantial use, thereby striking a balance between public interest and private rights.

-By Shlangha Mandal