The moral underpinnings of justice are highlighted by the notion, “Let hundred guilty be acquitted but one innocent should not be convicted,” which places the protection of the innocent first. However, the tragic tale of Atul Subhash shows how this idea can backfire when rules are applied improperly, causing irreversible damage.

Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, which is meant to protect women, was abused against Atul, a normal man with ambitions. This rule, which was created to protect women from dowry abuse and harassment, permits quick arrests in response to allegations, frequently without conducting an investigation. In Atul’s case, his wife took use of the legal system to create unsubstantiated accusations, which resulted in his incarceration, humiliation in public, and psychological suffering.

Despite no conviction in court, the accusation itself became Atul’s punishment. Society labelled him a criminal, his reputation was damaged, and his family including his aging parents had to endure the experience. He felt hopeless as a result of the emotional agony of humiliation and loneliness combined with the financial strain of legal disputes. Atul eventually committed suicide, leaving a note begging for his innocence to be acknowledged.

The one-sided nature of these regulations, which frequently presume guilt without due process, is highlighted by Atul’s case. Although the goal of these regulations is to safeguard women who are at risk, when they are applied improperly, they become instruments of harassment against defenceless people.

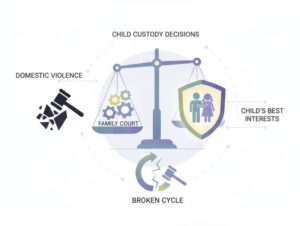

In order to prevent abuse and guarantee justice, this tragedy necessitates immediate legal reforms. Achieving a balance between protection and justice requires mandatory investigations before to arrests, accountability for false accusations, and assistance for those wrongly accused. Atul’s sacrifice ought to act as a spur for reform, reminding people that justice involves more than just punishing the criminal; it also entails protecting the innocent from unnecessary pain.